Partnerships face unique tax challenges that most business owners don’t anticipate until it’s too late. The difference between a well-executed tax strategy and missed opportunities can cost thousands of dollars annually.

At My CPA Advisory and Accounting Partners, we’ve seen firsthand how proper tax planning for partnerships transforms bottom lines. This guide walks you through the strategies, pitfalls, and actionable steps you need for 2025.

Partnerships operate under pass-through taxation, meaning the entity itself pays zero federal income tax. Instead, all income, losses, deductions, and credits flow directly to each partner’s personal tax return based on their ownership percentage or allocation agreement. This structure creates a fundamental advantage: income gets taxed only once at the partner level, not at both the entity and individual levels like C corporations. The IRS requires partnerships to file Form 1065 by March 15 each year, but this return is informational only. Each partner receives a Schedule K-1 detailing their specific share of ordinary business income, rental income, capital gains, Section 179 deductions, depreciation, and dozens of other tax items. That K-1 then flows to the partner’s personal return, where they report and pay tax on their allocated share. This means a partner earning $100,000 in partnership profits owes federal income tax on that $100,000, even if the partnership distributed only $50,000 in cash. The pass-through structure gives partnerships tremendous flexibility in allocating profits and losses among partners, but it also demands precision in tracking basis, distributions, and each partner’s tax position.

Partner basis represents the tax foundation for every partnership transaction. It starts with what a partner contributes: cash plus the adjusted basis of any property transferred into the partnership, plus their share of partnership liabilities. From there, basis increases annually as the partner’s share of ordinary income, capital gains, and tax-exempt income accumulates, then decreases as distributions reduce the account, losses reduce it further, and non-deductible expenses lower it. The critical rule is that a partner cannot deduct losses beyond their partner basis limitations loss deductions. If a partner has $50,000 in basis but the partnership allocates them $75,000 in losses, they can only deduct $50,000 in the current year; the remaining $25,000 carries forward indefinitely until they have additional basis. This limitation catches many partnership owners off guard, particularly in real estate or equipment-intensive businesses where depreciation and Section 179 deductions generate large losses. Additionally, when a partner receives a distribution, it reduces their basis dollar-for-dollar. A cash distribution above a partner’s remaining basis triggers immediate gain recognition. These mechanics mean that sloppy basis tracking leads to missed deductions, unexpected tax bills, and disputes with the IRS. Track basis quarterly, not annually, especially in partnerships with significant depreciation or substantial distributions.

Most partnerships start as general partnerships or limited partnerships by default, but the real tax decision is whether to elect S-Corporation treatment for a multi-member LLC or whether to keep the partnership structure intact. This choice hinges on net income and self-employment tax exposure. An S-Corporation election requires the owner to pay themselves a reasonable W-2 wage and take the remaining profit as a distribution. The wage portion is subject to payroll taxes (approximately 15.3% combined for Social Security and Medicare), but the distribution portion avoids self-employment tax entirely. For partnerships, all ordinary business income faces self-employment tax at roughly 15.3% on 92.35% of net earnings. The breakeven point typically occurs around $60,000 to $80,000 in net annual income per owner. Below that threshold, the extra accounting and payroll complexity of an S-Corp election usually outweighs the tax savings.

Above it, the self-employment tax savings can exceed $5,000 annually for a single owner earning $150,000 in net profit. A partnership with four equal partners each earning $100,000 in ordinary income would collectively face approximately $55,000 in self-employment tax; electing S-Corp treatment and splitting each partner’s $100,000 into a $60,000 W-2 wage and $40,000 distribution could reduce that combined self-employment tax burden by roughly $18,000. The election itself requires filing Form 2553 with the IRS, and once made, it applies to all members equally. State tax implications also matter: some states impose entity-level taxes on S-Corps that negate federal savings, so model your specific situation before deciding.

With these foundational tax mechanics in place, partnerships can now focus on the specific strategies that maximize deductions and minimize tax exposure in 2025.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act made 100% bonus depreciation permanent for qualifying property placed in service after January 19, 2025. This is not a temporary provision that expires in 2026-it is permanent law. For partnerships investing in equipment, machinery, or certain real property improvements, this means you can deduct the entire cost in the year the asset goes into service, with no phaseout. Qualified Production Property used in manufacturing now qualifies for immediate expensing under Section 168(n) if construction began between January 19, 2025 and January 1, 2029 and the property is placed in service by January 1, 2031.

Section 179 expensing remains available at $2.5 million for 2025, with phase-out thresholds applying once total acquisitions exceed $10.25 million. If your partnership has delayed equipment purchases, 2025 is the year to execute them. A partnership acquiring $500,000 in machinery qualifies for a full $500,000 deduction in year one, reducing taxable income dollar-for-dollar and potentially eliminating or deferring estimated tax payments into 2026.

Domestic research and development costs now qualify for immediate expensing under Section 174A, retroactive to 2021 for small businesses meeting the gross receipts test. Partnerships with R&D activity can deduct these costs immediately or elect a 10-year write-off, with transition rules allowing deduction of unamortized costs from prior years. This creates a significant planning opportunity: partnerships that incurred substantial R&D expenses in 2021 through 2024 can amend prior returns to claim immediate deductions, generating refunds that offset 2025 tax liability.

The qualified business income deduction under Section 199A remains the most misunderstood partnership tax benefit. You can deduct up to 20% of qualified business income for 2025, but this deduction has phase-out thresholds tied to taxable income and W-2 wage limits that catch many partnerships off guard. Starting in 2026, income phase-in thresholds rise to $75,000 for individuals and $150,000 for joint filers, with a new $400 minimum deduction, making planning now essential.

The critical distinction is that guaranteed payments to partners do not qualify for the QBI deduction-only ordinary business income does. A partnership paying one partner a $50,000 guaranteed payment and allocating $100,000 in ordinary income can only apply the 20% deduction to the $100,000 portion. This mechanic incentivizes restructuring how partners receive compensation. Shifting a portion of guaranteed payments into profit allocations, where economically defensible, increases QBI eligibility and reduces overall partner tax burden.

For partnerships with multiple owners, aggregating eligible qualified trades or businesses under Section 199A regulations expands deduction capacity. A partnership operating both a consulting business and a software development business can aggregate them if commonly controlled, potentially qualifying for a larger deduction than treating them separately. Additionally, partnerships should evaluate which trades qualify as specified service trade or business activities, which face additional limitations.

Real estate rental partnerships that meet the safe harbor requirements under IRS News Release IR-2019-158 qualify as trades or business for QBI purposes, unlocking the deduction for real estate-focused partnerships. The deduction interacts with W-2 wages paid to employees and the unadjusted basis of qualified property, meaning partnerships with significant payroll or equipment basis can claim larger deductions even at higher income levels. Partnerships should model QBI deduction scenarios quarterly, not annually, because timing decisions made early in the year-particularly regarding when to recognize income or accelerate deductions-directly impact the final deduction amount on the partner’s personal return.

These deduction strategies set the stage for partnerships to substantially reduce 2025 tax liability, but maximizing them requires attention to timing and coordination with state tax planning, which presents its own set of opportunities and complexities that partnerships must navigate carefully.

Most partnership tax disasters stem not from complex strategy failures but from basic execution errors that compound over months. The same preventable mistakes appear repeatedly: partners who cannot substantiate basis calculations when audited, partnerships that misclassify guaranteed payments as distributions and trigger unexpected tax bills, and owners who miss quarterly estimated tax deadlines because no one assigned responsibility for payment dates. The IRS reported increased partnership audit activity in recent years, with large partnerships and those claiming substantial special allocations facing heightened scrutiny. Poor documentation is the primary reason these audits escalate into penalties. When the IRS questions your basis calculations or the economic substance of special allocations, you need contemporaneous partnership agreements, capital account statements, and allocation schedules. Without them, the IRS assumes the most unfavorable interpretation and assesses additional tax plus accuracy-related penalties of 20% of underpaid amounts. One partnership claimed $150,000 in depreciation deductions across multiple partners without maintaining separate fixed asset registers or cost-segregation studies. During audit, the IRS disallowed $80,000 of those deductions, assessed $16,000 in penalties, and demanded amended K-1s for three prior years. The cost of reconstructing documentation and responding to IRS inquiries exceeded $25,000 in professional fees alone.

Documentation failures intersect directly with compensation misclassification, which creates a second category of costly errors. Partners often treat guaranteed payments as distributions to simplify bookkeeping, but this distinction matters enormously for self-employment tax and QBI deduction eligibility. A guaranteed payment is ordinary business income that flows to the partner’s K-1 and subjects them to self-employment tax at 15.3% on 92.35% of net earnings. A distribution is a return of capital that avoids self-employment tax entirely. A partnership with four equal partners, each receiving $75,000 annually in what they thought were distributions, might discover during an IRS examination that those payments should have been treated as guaranteed payments. The self-employment tax exposure alone could total $35,000 across all partners, plus interest and penalties. The distinction also affects whether income qualifies for the QBI deduction. Guaranteed payments do not qualify; ordinary income does. Misclassifying a guaranteed payment as a distribution reduces the partner’s QBI deduction dollar-for-dollar, potentially costing another $4,000 to $8,000 per partner depending on their tax bracket. You should document the economic substance of every partner payment in the partnership agreement before the year starts, specifying which payments are guaranteed and which are distributions, then reconcile actual payments to that agreement quarterly.

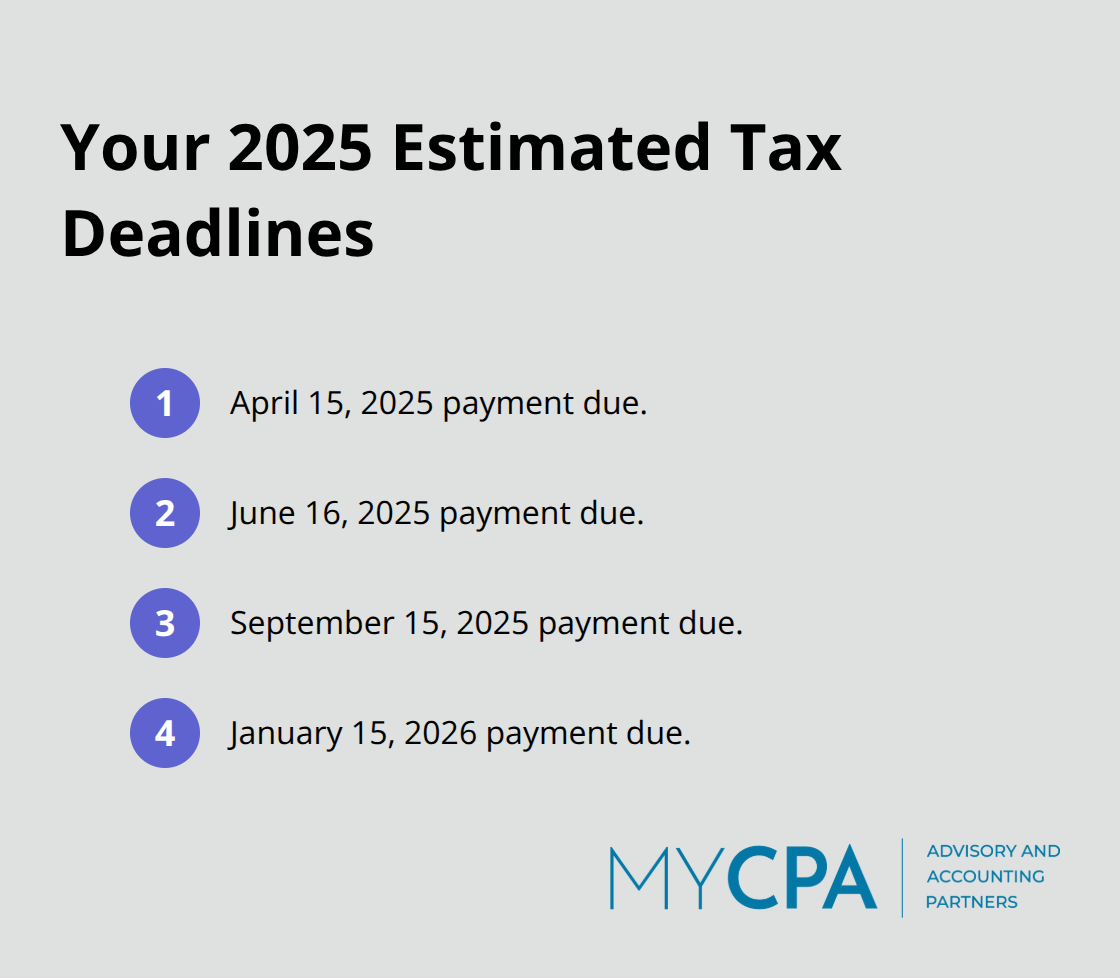

Estimated tax payments represent the third failure point, and this one carries immediate financial consequences. Partnerships themselves owe no federal income tax, but partners individually must pay estimated taxes on their allocated income quarterly if they expect to owe more than $1,000 in tax for the year. The 2025 estimated tax deadlines are April 15, June 16, September 15, and January 15, 2026. Many partners miss these deadlines entirely because the partnership does not remind them and they assume the partnership will handle tax obligations.

Missing a single quarterly payment triggers an underpayment penalty calculated from the due date of that quarter through the actual payment date, compounding at roughly 8% annually. A partner who should have paid $10,000 quarterly but paid nothing until filing their return in April 2026 could face $800 to $1,200 in underpayment penalties alone, on top of interest. Partners with irregular income or those who received large distributions mid-year often underestimate their tax liability and underpay significantly. You should calculate each partner’s estimated tax liability by September 30 of the prior year, communicate the amount to partners in writing, and ideally establish a reserve account or withholding arrangement to fund those payments directly from partnership distributions.

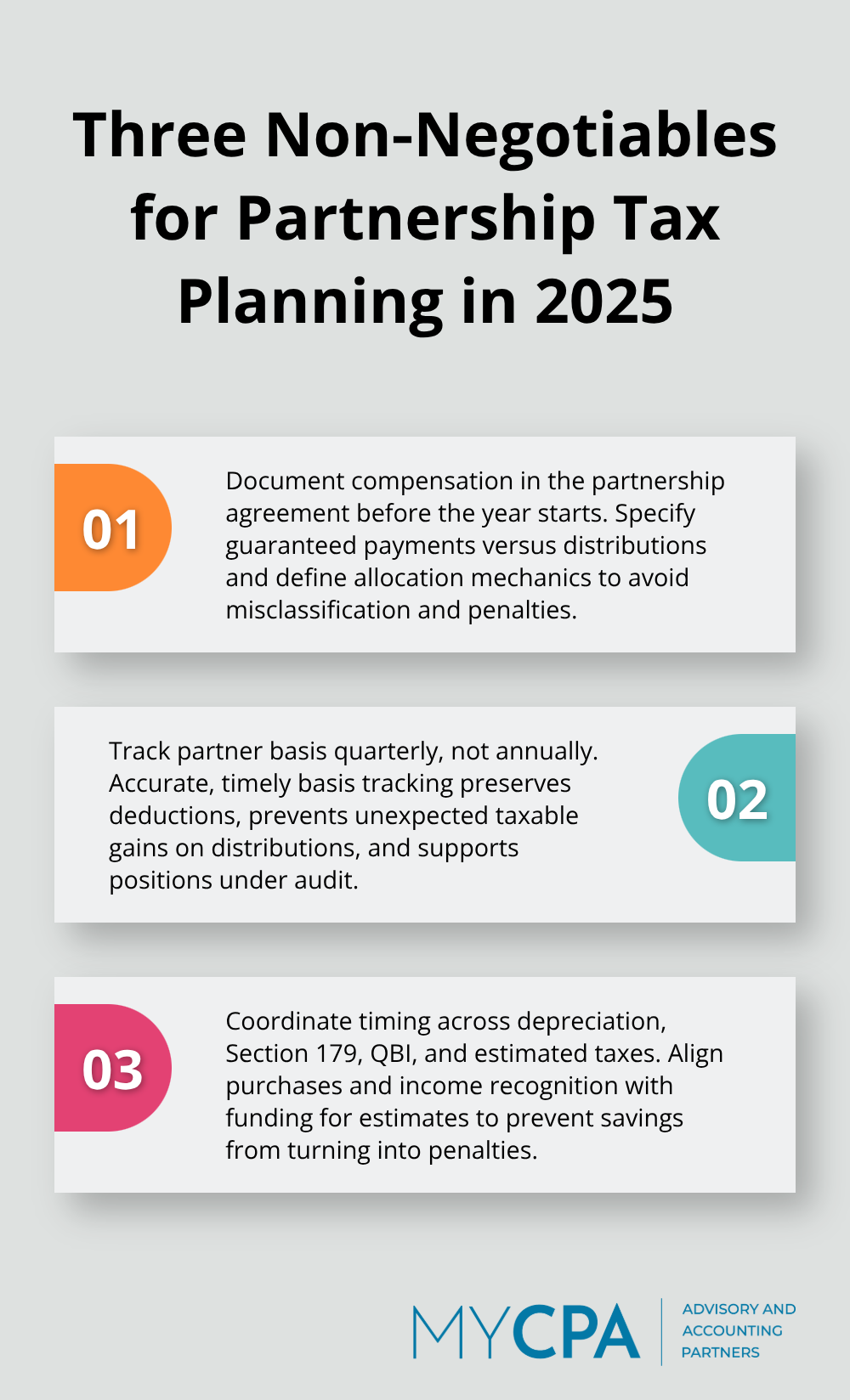

Partnership tax planning for 2025 requires three non-negotiable actions that separate successful partnerships from those that leave money on the table. First, document everything in your partnership agreement-specify how partners receive compensation, whether payments are guaranteed or distributions, and how income allocates among owners. Second, track basis quarterly, not annually, because a partner who cannot calculate their basis accurately during an audit loses deductions, triggers unexpected tax bills, and pays penalties on top of the original shortfall. Third, coordinate timing decisions across depreciation, Section 179 expensing, QBI deductions, and estimated tax payments so that accelerating equipment purchases into January 2025 does not create a cascade of estimated tax problems that cost far more than the original tax savings.

The complexity of partnership taxation means that professional guidance becomes essential for partnerships earning more than $250,000 annually or claiming substantial special allocations. The IRS audits partnerships at higher rates than individual returns, and audit costs escalate rapidly when documentation is incomplete-a partnership that invests $3,000 to $5,000 annually in professional tax planning typically recovers that investment through a single avoided penalty or optimized deduction strategy. We at My CPA Advisory and Accounting Partners work with partnerships to model tax scenarios, coordinate entity-level and partner-level planning, and ensure K-1 accuracy before partners file their personal returns.

Schedule a tax planning review before year-end and bring your partnership agreement, recent K-1s, and a list of planned capital acquisitions or significant business changes. We can model the impact of bonus depreciation, QBI deductions, and estimated tax obligations specific to your partnership structure, turning reactive tax compliance into proactive tax planning for partnerships that saves thousands of dollars annually.

Privacy Policy | Terms & Conditions | Powered by Cajabra